Yes, because he never did a thing like that before, wondering how he might look caught in the gesture of asking, a gesture of language or between bodies or of the body alone. In a loft in Greenpoint with the men all working on novels about men working on novels, he talked in that slow deliberate way they do to be admired and I said yes, let’s go someplace else; yes because he never seemed to consider the demands of an imagined audience, he only laughed and said God you people must be miserable all the time.

Yes because you couldn’t picture it really, his cheating and going to rehab and coming back in that pleading way they do to be forgiven, and yes even then; in two years he will tell me how he used to change out the books on his nightstand so I wouldn’t think he was stupid if I thought all men were the same; the sirens or the Angelus bells will be going like mad in Park Slope and it will be the one true thing he says in his life.

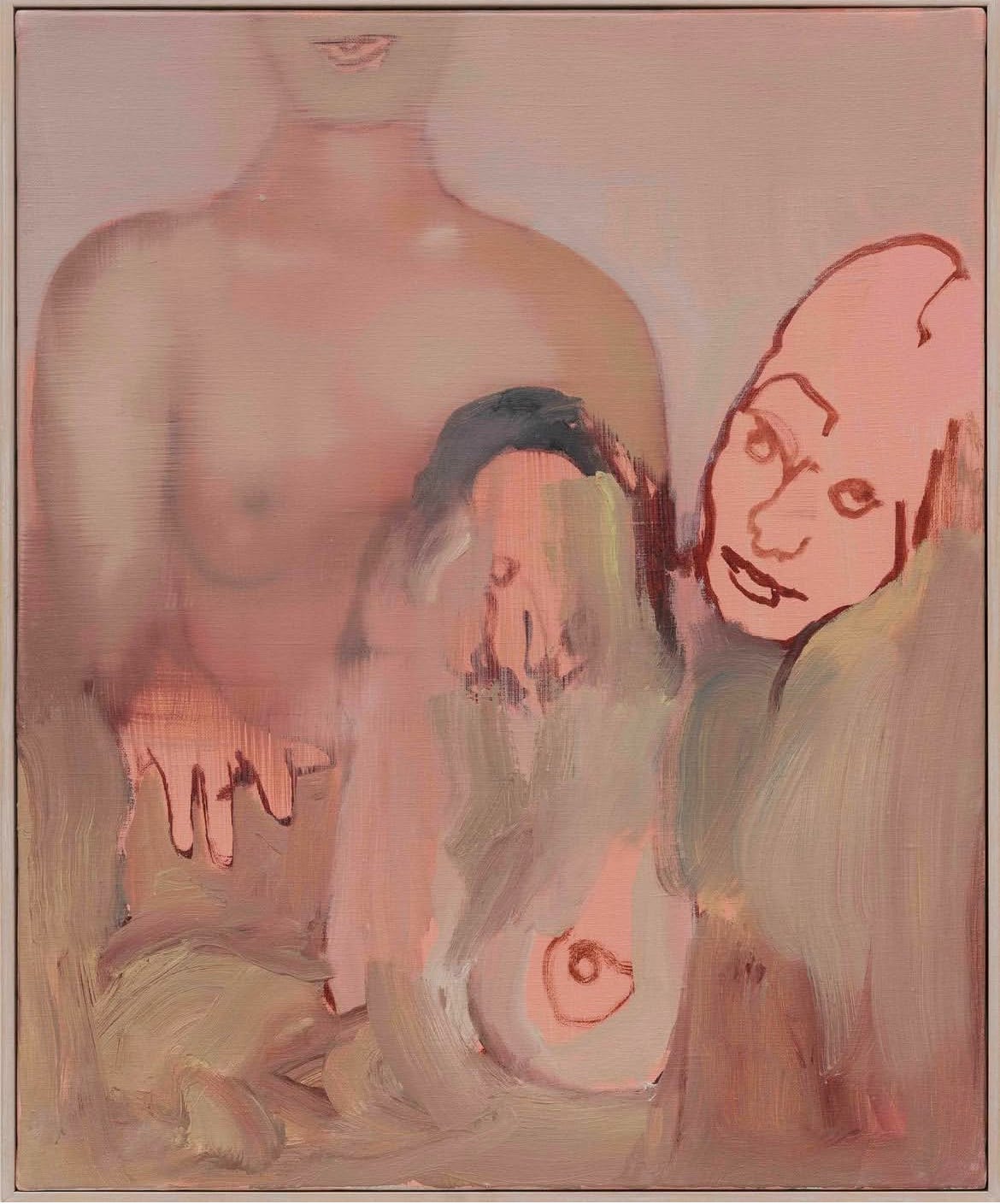

Maybe at one time he would have fallen outside the range of my sexual interests — on account of his age or his flatlining acting career or the daddy implications. Maybe at one time I was the kind of woman who believed sex should not be exchanged for power, not even with the implicit knowing. Maybe I believed I would not ever stoop as low as loving him, love being an abstract chase of youth. Maybe at one time I was the kind of woman who did not know that she could hold power up close, ride it, say the name it gives itself. These times, if they existed, will leave a slim space of return, I think, for when I tire of the hunt. I feel it, this tiring, in the mornings when the beauty of him recedes and we become dull to each other. Not boring, not at all boring — just dull as in the blunted knife, a bedside lamp in a trucker motel, lazy head. A George Rouy painting, that lucid blur. I welcome the dullness of us, the way it shores up a life.

Yes, I said to him, probably deep down I did think you were stupid, or that old men were all a certain way. Yes, because it was June, that obvious month, when I read to him the passage where Molly recalls flowers in the hair of Andalusian girls and the rich man and the young poet of her husband before he was her husband, she thinks of giving him head on the windward side of the mountain the day she said yes I will Yes. I did my best Barbara Jefford and, looking up expecting to find him moved beyond all reason as I’d been, saw that he’d fallen asleep. Must have been the breathless meter of a wife speaking her first words in 1904. Yes, deep down I did think he was a little stupid, or just that we were not under the same illusions about love. (I thought we were in it; he did not appear to think at all, but then what kind of person “appears” to think? What kind except the kind he is, lecturing in that circular way they do to be praised.) I pictured all the girls who’d gone to where Molly was a flower of the mountain and the loud streets that were supposed to lead to the second quarter of this century and instead left me here, still, in the first quarter of a life. The sleeping man turned onto his side, swaddled in the relief of my silence. Sleep, I longed to say to him, but he already was, and giving permission might wake him. I pictured the dark rooms I’d slept in and the men writing novels about men writing novels and the AA sponsor I’d slept with during the first relapse and the sleeping man of this present moment and thought Well, as well him as another, and called myself a car.

Outside, two women stood, one on the sidewalk, the other on the front steps of Saint Mary of the Assumption School. The one on the steps was hunched over—I assumed in some postpartum agony like the Blessed Virgin in the Nativity, given how Catholic this scene had just become; or laughing, bent over with it. She straightened up as a pair of teenagers drew close: the girl was slouching so as not to appear taller than the boy. It was raining or looking like rain, and the couple had three more blocks before they could reasonably expect to find an awning to stand under. It did not matter—they were together at that age when boys and girls pull at each other somehow, without speaking or really touching, they just know. The girl, arriving now at where the Saint Mary’s women and I were occupying opposite sidewalks, straightened her posture just as the woman on the steps had done. I tried to diffuse what I sensed was already a memory — a permanent, necessary intersecting of lives — by looking at my phone. Looking at my phone and picturing us all there, each wondering how we seemed to the others, shifting in our new, insane kind of narcissism, the paranoid love affair a person arranges between herself and anyone who might be watching.

I now picture it differently. It was I alone who shifted, I alone who wondered. There was no one around, but I feared CCTV from a storefront somewhere was sure to make a note of me.

Yes, because he never behaved like that, just admired the rain and moved quickly, happily out from under it. Yes because there was that dinner party that winter when the professor's wife, trying to prove a point, asked what we’d do if we could go back in time, and he said I know you want me to say I'd kill Hitler, but I would buy land, I'd buy like all of California. Then I'd been so embarrassed for saying I'd kill Hitler like everyone else.

Yes, because say there is a woman who makes art like the sex she has, indulgent, self-absorbed. Say the woman is twenty-five, which is both too young and not young enough to make her interesting. Say she acts her age. Say the man has lived twice as long. He talks sometimes with that put-on inflection of young sleaze, other times with the comforting assurance of his middling age, which is the comfort the woman prefers to stow away in. Say the man declares that every year since she left Columbia the woman's writing has gotten better, funnier. Say it’s a bit like getting an earnest pat on the head, like seeing herself in his eyes and seeing a girl who is mildly intelligent and hugely adorable, and she’s just relieved to learn that a girl can be both. Say the woman finds the man indulgent, self-absorbed — say she faults him with all the moral failures men his age levy against their strange young girls. Say she likes it, finding him this way. Say that when the dinner party is over, he tells her Don’t be embarrassed, killing Hitler was the obvious choice.

I told him yes, I think I should have the option to exchange sex for power; yes it might have started like that with us, yes I’d like them to stop throwing out powerful men for that sort of thing. It seems to me an equal enough exchange, consolation taking the kindred shapes of sex and opportunity. I told him yes, leverage; yes, something else, something like being in love with him, if I may decide for myself. I have lost friends who believe I do not have the autonomy to choose him, that only he can hunt, take, want. They treat women like children, first off the boat.

Forget the rain; forget the woman and the other woman and the teenagers passing through. Someday, when the sleeping man leaves me, it will be because I shifted and wondered. It will be because I am sick with lust, lust which is a symptom of something worse, and still too faithful, too needing. He’ll say Go back to Greenpoint with your little friends—go and pretend you’re a woman rediscovering herself after a divorce—I’m sorry—you look so pretty with the light draping like that—you should slap me for not loving you anymore.

On our second date he called me Emma. It was close enough; I answered to it.

Yes, because the first night on the sidewalk in Greenpoint we were waiting for two cars to take us apart, until he changed my mind or I changed his. I thought of others, of the boy in Missouri when I was not yet sixteen, of cul-de-sac swimming pools and John Cassavetes and my father; of the Catholic girls walking home, their skirts cuffed above the knees; college boys smoking under bar marquees, famous perverts under pressure, under the faucet of digital heat, and him under me. I asked him to ask me again and yes, I said I will, Yes.

This is very good as a piece of imaginative writing but also true: an incisive commentary on the moralistic stupidity that passes for enlightened right-think these days. You seem to know it well (as do I, unfortunately).

you are GOOD.