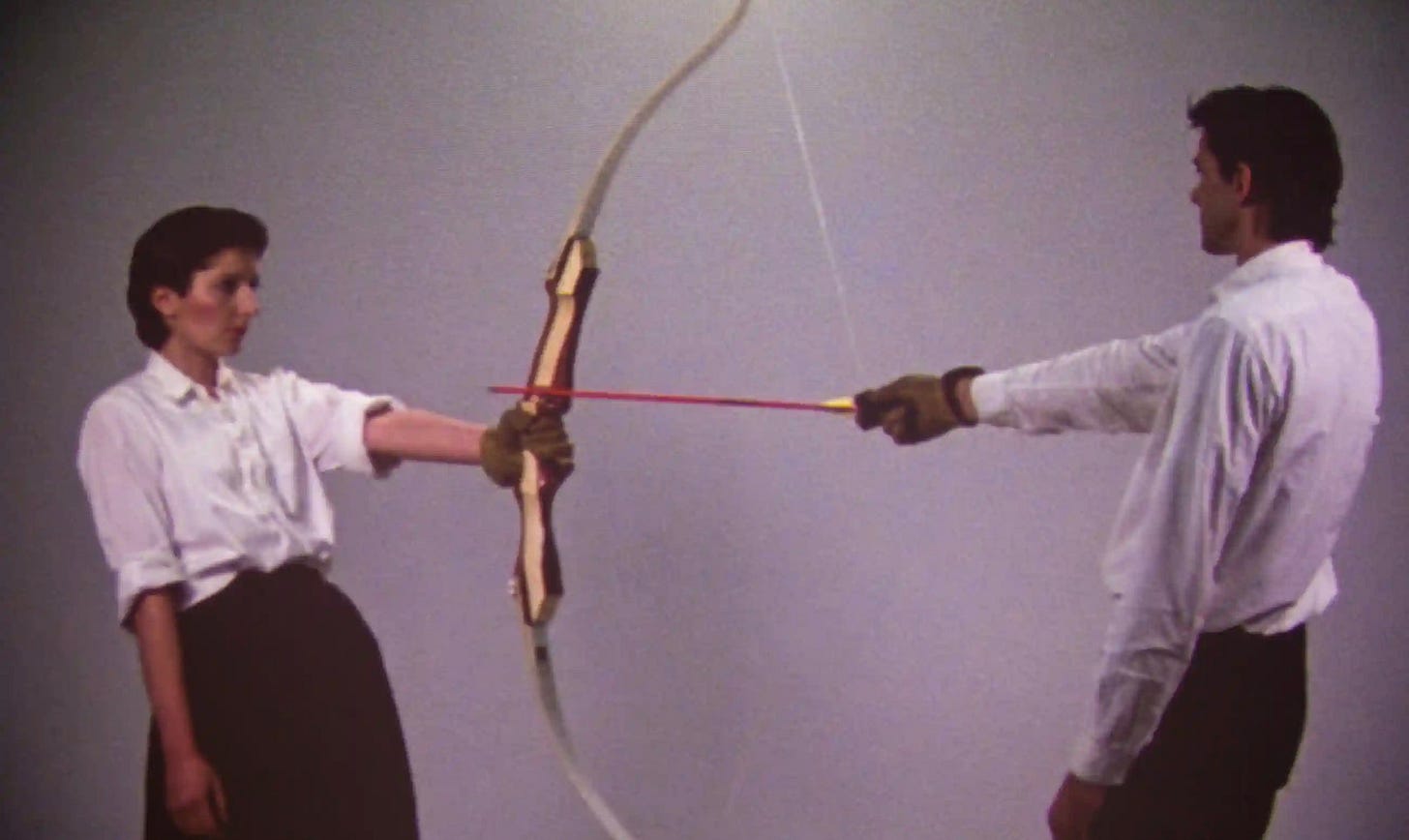

Rest Energy

I was practicing softness and gentleness in the bathroom mirror. I drank from the sink, lifting shaky handfuls of tap water as I waited for shame to take hold and make use of me. I had not been ashamed as I climbed off of him, but acutely aware of shouting from the street below, the weight of my bladder, the relief of sex being over, of the privacy restored when our bodies came apart. The mirror was flecked with soap scum, a dark rim of rust. I wiped it down with a wet cloth, causing streaks to form as it dried. This new composition warped my features, making softness and gentleness difficult to appraise.

Reid was asleep on his side when I came back to bed. How routine it is, in scenes like these, how similar one encounter to another, how impersonal my desire turns out to be. These people, their boring jobs and hometowns and numbers of siblings: they are jock-bodied boys, tired old guys, the men in between. I crawled into the space around him—paternal, so unlike the refined, waifish bodies I was used to. I beg and am sated, I often think; the partner is incidental. But just as often, I look at the nape of a man’s neck, his dear brown head while he is sleeping, and I need him particularly and completely; I picture us in the morning, when we will put on our clothes to walk the streets like humans and get onto the train cars that take us apart. The truth of my body is that it was made for this work. It is soft and small, it yields: rape me. Still it is a body, hysterical for holding someone.

He had no curtains to blot out the light. Under us, the city was loud and new, a romance. I tried to take stock of his objects, to remember him by them—a coat rack, a narrow window that opened onto a concrete patio over the Chinese restaurant, an old tennis trophy, plain walls. There are things we expected to have by now that we don’t.

I left before he woke up. I did not want to go but hoped my absence would disappoint or disorient him, a small assertion of power where there was none. I knew when I left that I would never see him again, and I never did. Sophie called to say she would be gone when I got back to her apartment but had left a key under the mat. She asked about my night. I told her that I’d chipped away at all my happiness while Reid slept and now I was feeling its absence—not in those words but in some equally ridiculous way, testing the limits of her sympathy. She said something to the effect of “Men, right?” and I said something to the effect of “Right,” even though it wasn’t quite right. She sounded tired, sick of me coming to stay with her in Park Slope and then spending half my nights with some guy on the Lower East Side—that’s what she called him, “some guy.” Sophie knew Reid from college but for some reason insisted she didn’t remember him. “Well,” she said, annoyed but gentle, waiting for me to go back to Boston, “He’s an idiot, from what I know.” She knew him. We had a lot of the same friends. It annoyed me, her treating Reid as this peripheral, foreign person as a kindness to me. She predicted that it would not work out, and denying his relevance would soften the blow. Sophie has always shown me this protective impulse, even though what is done to me, most of the time, is what I do to myself.

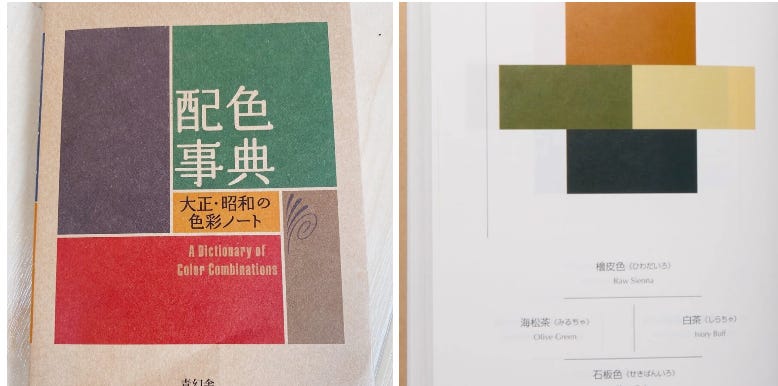

I walked slowly and for a long time before receding underground to get the train. In my big coat and slept-in makeup I thought I disappeared nicely into the flock of people walking, with or without intention, past the glittery storefront Christmas displays; the invisible homeless, whose appeals to human sympathy went ignored; a cigar shop; the art library where I had, in the span of two years, accrued a $40 fine in Sophie’s name by failing to return A Dictionary of Color Combinations. She had stopped bringing it up after I insisted several times that I’d lost it. And anyway, I was doing her a favor, a misdeed she could cash in for points in some future dispute.

I knew where I kept A Dictionary of Color Combinations. It was in an unmarked box in a linen closet at my parents’ house in St. Louis.

I thought it would be useful to my pursuit of becoming a more discerning person. There are 348 colors named in A Dictionary of Color Combinations, as obvious as Antwerp blue or pearl, and as elusive as vinaceous tawny, fawn, vistoris lake. You see everything, and everything has a name: the St. Louis tarmac, loud cities dotting the coasts, a bar fight, cold air from the Ozark highlands on what they are calling the first day of spring. Hay’s russet, slate, urchin, Corinthian pink. Because the colors were named in Japanese, the English reader gets an imperfect translation passed through many hands. Changes to the process of color printing, zinc plates replacing lithographic stones, transliterated in the printheads of modern CMYK machines, have further undermined the integrity of Sanzo Wada’s original colors. The text is often taught in fashion schools, or studied recreationally by the very fashionable, who have or pretend to have expert eyes and honed palates. And you, the rest of you, hurry toward the end of this life with your small and illiterate sensory faculties, and you expect them to believe that you are happy.

I missed my train to Boston. I wasn’t doing anything really, just walking around. This sort of thing happens to me often, plans upended by idleness, and if I believed in God or the universe at that very moment I might have stepped outside of myself to consider the pattern, but I didn’t. Instead I boarded a bus in front of the Lucky Star on Canal Street, where beside me a woman bounced an inconsolable child in her lap. Other people’s children signify the problem of time in the body, age and purpose and the extraneous womb. When I encounter a child, I really encounter it. It’s like I find out about them for the first time, every time. That’s what that is, I think. I’ve heard of that happening. All my life there were mothers. The older girls on my street who watched me after school, mothers; the school nurse who admonished me for faking a case of lice so she would touch my hair, a mother. A friend’s unplanned baby in a sling, his pudgy darling jowls, a mother. A store clerk fetching me another size of something; the dry cleaner’s seamstress adjusting the hem of a communion dress; the long stupor of a morning bus; petty cash. Mothers.

I thought the whole way of Reid, who claimed to have an object permanence problem and joked that I might solve it by becoming a permanent resident of the city. If only I had been smart enough to build time and money into my life for being bored and broke and impulsive, moving around, changing cities and jobs and friends, I could have accommodated his object permanence problem without sending long-distance nudes and embarrassing myself trying to be pretty on the internet. It didn’t matter: the obsession that bloomed was conditional and explosive. He wasn’t very funny or very interesting or very beautiful, and it didn’t matter, it has never mattered with any man. I would take stimulants to delay hunger, becoming the pious starving girl of my youth; when my weight rose above 92 I would react violently. Without eating I would resume drinking and fucking, if only to distract from the possibility that he did the same. I would stop seeing friends, I would spend all my money, I would become the desperation that no one could love.

I mark time this way, remembering almost nothing of my life: long stretches of nothing, punctured by an obsession with someone, then nothing again.

Midwinter in Boston, vanity walled up in me as I looked for myself in shop windows and train reflections and the faces of other people. It made me pathetic with need, it made me mean. I let dishes pile up in the sink while my roommates moved in silent rage through the apartment. I ignored my friends. I no longer cared about their comfort. Who among them would understand, for example, that I didn’t envy their grad school stipends, their contributions to the literature on late-stage capitalism and the compromising effects of Botox on the ability of the Real Housewives to empathize and emote? That my sole and driving vision for my future was only ever to be beautiful, beauty being life’s one admirable and worthwhile trick? To be beautiful in the way of wet-lipped stars on TV; in the way of the dogwood that bloomed without company or cause outside my childhood bedroom each spring? To be beautiful in the way of breasts; to drape small gold crucifixes between them? To loiter where girls were pretty and stupid under strip mall awnings and movie marquees, lying about their ages, pulling smoke from their lips? That I can only be certain I am a woman by invoking something primal; that I prefer beauty to intellectual inquiry or craft; that I want to watch women get into the cars of bad men in the movies, men with tempers as thin as the stockings of the women by the road.

“Could you just wash them?” Rachel said, looking at the dishes. “At least the forks and stuff.” She was so nice. I felt sorry for her.

“I was about to. I will.”

It’s nothing personal. Reid did not invent obsession, and it had very little actually to do with him. I had loved someone before, someone I did not deserve, and every person afterward was measured against him and found badly wanting. We were younger and still sort of afraid in our bodies, fucking under the duvet like they do in PG-13 movies. I woke up in anxious fits, feeling around on the nightstand for a bottle of klonopin as he went on sleeping into the late afternoon. Sometimes I touched his face to console myself, traced his eyebrow, felt his soft delicate ear and nearly cried. I took care of him in the morning, picking the clothes off his floor, putting the water on for his coffee before he got up. I tried to bring a sense of irony to it, the performance of this domesticity, this woman-ness. Once, when we showered together in a hotel room in Mexico, he turned me around and washed my hair. It was a wordless exchange: he sudsed up the top of my head while my arms hung at my sides and water hit my face. Then I understood there was no irony in anything—I was folding his clothes, I was bringing him coffee. He carted me around to run errands when I crashed my roommate’s car and lost all driving privileges, materially and socially. We worked in equal measure to make it harder for the other person to exist alone. I gave up my independence to ensure that he also lost his. I had never been as relaxed or as immaterial as in that hotel room in Mexico, when he stood mechanically over me, washing my hair.

We began fighting, badly, not long after that vacation. We said the worst things we could think to say to each other, and when that wasn’t enough, I went out and got drunk and flirted with other guys in front of him, and he stayed sober to hold it over me in the days to come, cold and punishing as I pleaded and crawled. I tried to look at my boyfriend with big solicitous eyes, to exhaust his reserves, make him want me as I knew he had once and might again. But it was over, and I was the cause. He had seen the part of me that wanted to have as much of people as possible—their desire, their disappointment, their attention—and it had fissured the mythology of the sweet girl he liked. I watched him recoil at every act of desperation, my hand on his arm when he was rude to a bouncer, the very fact of me still being there, a stray dog that followed him around. I wanted to be a different kind of woman. The kind who had no sense of urgency, who showed restraint, laughed when she was supposed to and didn’t when she was not; the kind who needed no one, who could stop herself just short of sex. Who, when someone claimed to love her, kept a level head and said nothing and thought Love me? Does he think I’m stupid?

When he asked me what I wanted (from sex, for dinner, out of life) I told him I didn’t know. It is a question they all ask, in one way or another. What do you want? What I really wanted, what I could not explain to him, were the stories of boys and men in the movies, young actors looking at each other across busy rooms. I liked to watch these men fuck and imagine how it might feel to be one of them, but more than that I liked to watch them have a conversation: there was a quiet, assumed equality between them, a mutual respect that did not need to be earned. It is the unspoken recognition of another person’s total humanity that cannot exist between a woman and a man. (You think he can hear you, you hope your whole body will act as a refusal, but he can’t, and it doesn’t. After the initial pain of forced entry, your body recognizes what is happening and accommodates it. He pushes your face into the bed and you let yourself become pliable until this pain is indistinguishable from all the pain before it, the pain you asked for.) Resign yourself to it, I think. If our quiet, assumed equality cannot exist, if we can never really understand each other, then we do not need to try. We do not need to delude ourselves into thinking our men know us or that we know them, or that we love each other really, or that we want to.

If I tried to explain it, he might laugh, not understanding the severity of our situation. Or he might pull away, finding this talk perverted and me strange. I didn’t want to explain the invisible laws that kept us apart, but to fall asleep wrapped up in him as though I didn’t know they existed. It was something I wanted in those years from almost every man I met: to be close to him physically, as close to his body and to knowing him as possible within our given constraints. This impulse is a symptom of my particular addiction, which is not to sex but requires it. It is the addiction to the idea of knowing men as I know women, and to being known by them as they know men; it is the addiction to something unnatural, heterosexual, intellectually wrong.

I am your woman,

and your woman lies down, an animal taking a bullet.

Part 2. Everyone You Know

In the January of my obsession with Reid, I began to inhabit him, to notice women the way I imagined he would. I noticed the clothes they wore, the shapes of them, how they moved and insinuated nudity. I noticed how they swept up their hair on unseasonably warm days, their features relative to mine, how they ducked in the rain or stared straight ahead while waiting at a crosswalk. How they gave the impression of power: without hardness or implied violence, all the pretense of a man. I confused this noticing at times with attraction, which in some cases it was, and went home with them, the most perfect women in the world. I imagined I was him, mindlessly fucking these nameless, uninteresting girls for no particular reason, each one a means to no particular end.

The only one who ruptured the unfeeling, cold quality of him—of me pretending to be him—was Olivia, who had rich parents and was trying to live for the first time without their assistance, playing the part of a struggling artist. I liked her a lot: she reminded me of my terrible friends, boring, gorgeous, post-post-ironic, warmed by insulating wealth. She was a painter, living alone and taking long afternoon naps until the embarrassment of accepting her parents’ money caused her to get a day job. I loved to watch her paint. She had no craftsmanship, no eye, no sensitivity. She bleached her eyebrows and wore little shorts with BABY rhinestoned on the ass and a kids’ I Love NY t-shirt from a kiosk in Times Square. She was the aftermath of the dude auteur, saving herself from misogyny by staking a claim in it.

Her wealth came, like all wealth, from nothing and everything, industry and oil rigs and politics: her parents were a financier’s daughter and a media baron’s son; they were patrons of the local arts; they held stock in a domestic airline. She had tried to develop a gambling habit but could not commit to doing such specific harm to herself. She launched an OnlyFans, quickly gathering a small but devoted audience. Behind paywalls and graphic content warnings, the body concedes. Her viewership left their requests—a household tool, a certain texture, a landline, the carpet, cutting her hair—and she incorporated their feedback into the next work. She did not know the names or ages of her audience, the kinds of clothes they wore, the money they made, the positions they took for sleep. Or how they watched her: if they sat in front of computers in office cubicles, keeping her as an open tab while they typed and rode the coattails of the dotcom boom into the sunset; or if they lay in bed with their phones while a lover slept beside them; or if they showed her to the lover, trying to explain this texture, this object inserted into the body of this woman as—not a porn addiction the woman turned for profit—but as the final, terminal stage of human need.

When promoting softcore porn on her personal Instagram got to be embarrassing, Olivia found work in a pharmaceutical testing lab outside Boston, injecting mice with potent depressants and logging their responses to sensory and sexual stimuli. Most of the time they just slumped over, too tired to express hunger or yearning. She told me once, on a chaise lounge in her family’s country house in Connecticut, that she often felt like one of the mice, exhausted by the idea of sex or company, with no way to voice her troubles to the drug injector in a language they would both understand. She could have jumped from somewhere, she confessed, loving no one, but all possible outcomes—death, survival, an intermediate vegetative state—were as bleak as doing nothing.

It was hard to care about Olivia’s noncommittal threats of suicide in that house, where mounted on the wall of her father’s office was Gorky’s “Sun, the Dervish in the Tree,” which her family acquired for $3.4 million at a Christie’s auction in 1988. It isn’t that the suffering of the ultrarich is illegitimate, but that it is illegitimate to me. She would never consummate her suicide, never see an art project through to its end, never outgrow her self-immolating fantasies. That night she invited her friends up from the city and I watched her rub coke residue into her chafed red gums. I had gotten to the place where the people were cool, I thought, and everyone was just sort of standing around.

Nothing helped. Each time Reid reappeared in my life he gave me something to do: a reason to bathe, dress myself, make my bed or take the train to another city. I do nothing except what I do for men. The human things, daily chores, being clean and pretty and a part of the world. I might never leave my room without a man to prepare for. On my nights alone I remembered Reid was somewhere in the world, away from me but alive and incomplete as I was. I tried to sleep but was far too happy.

I found out I was pregnant on a Friday afternoon, late winter, early dusk. That night I took some of the oxycodone Olivia gave me when she got her boobs done, drank a bottle of good wine I’d stolen from her parents’ cellar, and vomited on the sidewalk in front of my apartment. I took a bath, waiting for the self-pity to sour into truth or violence. I woke up on the cold porcelain of the drained tub and called Kate, my best friend and only course of action.

“Okay,” she said, steadying me. “I’m pretty sure this happens all the time.”

“My mom had one in college,” I said.

“See? Everyone has had an abortion. Like literally everyone you know knows someone who has. Okay?”

“Okay.” I couldn’t think of anyone I knew besides my mom who’d had an abortion, but Kate’s conviction made me think she was probably right. “Literally everyone.”

Bored of my pregnancy, I told her about a dream I’d had with her in it: she had a pet bird, some bright elaborate thing, and I did not know how to interact with it, so I spoke in that put-on voice I use when I am unsure how to talk to babies or dogs. I was embarrassed by what I was doing, I told Kate, but I felt myself go on and on.

“You were looking at me like, Why are you talking to it like that? But I couldn’t stop. I didn’t know how else to talk to it.”

“I wonder what that means,” she said, knowing neither of us would look into it.

You might be thinking that the moral impulse here would be to stop boring innocent people with retellings of dreams. You’re right, of course, but that’s if you don’t know your audience. Some listeners will accept mundanity as a consequence of love. Kate and I are used to accepting mundanity from each other.

When we met, we were both drunk, both ecstatic and loud. She reminded me of an actress, but I couldn’t think of her name. It tugged at me for a long time and occasionally still does. She is a painter, a good one, but I didn’t know that when we met. If I had, I might have doubted her. Kate has a beauty and a lightness to her that, if not understood, could be mistaken for a kind of simpleness, a lack of serious thought. I think it is easy for her to be light, to be happy, because she generally likes things that are popular and is thereby guaranteed frequent encounters with the things she likes. A mango vape, bedroom pop, press-on nails, long weekends, the first signs of spring, blonde highlights, hot guys. I like those things too. She shows me how to make myself amenable to the world, and in that way she shows me how to be happy.

There is a love story in her bedroom in her Cambridge apartment with the yellow quilt and the line drawings on canvas and the palette-knife on the floor. It is a love story she told at the abortion clinic, where she stayed by my side, gossipped about the adult lives of people we knew peripherally in college, squeezed my hand as the doctor inserted the speculum, played with my hair.

As for the dream, it was simple: on the first day, God made language, and language made the rest. My dad said something like that when I was a little kid fighting with my brother. It was a child’s visceral, petulant anger: I did not yet have the words for it. The limits of language were the source of all tantrums then, as now. I ran to the vast blue room at the back of the house and sat huddled by the window, watching the lights of the near city. I fell asleep there, and when my dad came to scoop me up and carry me to bed, I pretended to stay asleep. When I woke again he had left to go west.

He had gone to the little town in California where he was raised and where everyone in his family but him had remained. When he and his brother were children and his parents were bright and barely twenty, they lived in the citrus groves. A square portion of land, a two-car garage, fresh oranges, a goat pen and Polish chickens, a koi pond. His father kept birds—the white-crowned sparrow, the lesser goldfinch—in a cedar shed behind the house. He brought them water and birdseed and installed screen doors for sunlight but did not set them free. They were still there when he died, or some iteration of them, generations along. Their domesticity had no end, no humane solution but a mercy kill. If they couldn’t survive in the wild air, I guess they died there in the cedar shed, matted and limp and heavy as black plums that ripened and fell from the branch.

At the end of his life, my grandfather was nearly blind, the irises of his eyes uselessly skimming the wet surface. When we played gin rummy, he gathered up the cards and tapped them square; my brother dealt and I whispered to my grandpa the numbers and suits of his hand. When he finally died, the paramedics carried him outside in an American flag. He’d spent the first third of his lifetime at war, the second protesting the draft and distributing agitprop for the Communist Party. If he believed in the Party, it was because he believed in the release of men from the labor that shortened and worsened their lives. In the final third, when I knew him, he was old with those alarming blue eyes and a coarse, thick voice that frightened me. These are the stories we tell about the dead: a perfect, three-act life.

Nobody thought he would have wanted to be wrapped up in a flag, but everyone let it happen, and some of the neighbors came out onto their stoops to watch. One man removed his cap as though paying tribute to a casualty of war, which in a sense he was. No one could resist a spectacle like that. Something changed in my dad then, or some existing thing was confirmed. He returned home older, and when he drank, a sentimental edge emerged that was not there before. He began to appear outside my bedroom to say goodnight, and if I said I was busy he would sing a sad little song from behind the door, derived from the William Carlos Williams poem: “I am lonely, lonely. I was born to be lonely, I am best so!” If he knocked when I happened to be in a friendly mood, and by adolescence such moods were scarce, I let him into my room, where I did homework on my bed until the first signs of morning. He kissed the top of my head: You’re a good kid, he said, again and again as though speaking it into existence. Good kid was the refrain of these sweet, earnest tempers he drank himself into—I think he went around knocking on mine and my brothers’ doors, waiting for one of us to accept his company.

Then, in the daytime, he watched us get into our cars and disappear into the world, pawning the love we’d been given.

Part 3. 1-800-LIFE

For a day or so I tortured myself with the thought of telling Reid. “I am pregnant,” I would practice in the mirror, before quickly adding, “But don’t worry, I’m getting an abortion. And I’m not asking you for money or anything.” These panicked reassurances took me out of my performance, and I had to look away—how stupid I was, practicing getting in the way of myself. I forced myself to cry, taking short fast breaths in the mirror. It wasn’t that I feared I might actually tell him, but that I knew I wouldn’t. I would take care of it, briefly pregnant, high on painkillers, woozy and nauseous from the procedure. I would bury this problem we made, the problem he placed in me, and save him the inconvenience of knowing about it.

I have seen my mom grow full and sick, keeping secrets. My dad wakes before dawn to put the coffee on and read the news on his phone in comically large font. By the time the rest of us are up, he is moping and must be consoled; he has found something wrong in the house, a flaw in its constitution, an invasive species in the yard, a benign mold in the rafters. I think he goes out searching for this feeling. He looks for a broken appliance so he can deplore its loss and complain of the money it will cost him to replace it. “Don’t tell your father,” my mom said quickly when I told her about the pregnancy. “It would destroy him.” I agreed. We go around like this, whole herds of us, protecting our men from knowledge.

The first available abortion was on Valentine’s Day, but that seemed desperate even for someone in my position—alone, anesthetized, prodded by gloved hands and speculums, I would be telling the story of my Valentine’s Day abortion forever—so I booked the next one, two days later.

I was determined to go to bed early on the night of February 15th. I was brushing my teeth and, not caring to practice softness and gentleness, looking at Instagram for the 10 minutes per day I allowed myself. I set this limit in the interest of being an intellectual person, instead of one who is, as my dad describes me, “beholden to the standards of beauty.” By which he means girly, by which he means anti-intellectual. I went to Reid’s profile and watched his story, which I never usually did for the same reason I left his apartment before he woke up—power, I think, which is the performance of apathy. The story, in its final hours, was from the day before: it was of him with a girl. They were celebrating Valentine’s Day. Toothpaste and spit ran down my chin as I stood there, forcing myself to look and keep looking. Then I rinsed out my mouth, got into bed, and turned off my phone. After a few minutes I turned it on again.

I studied the photo. The placement of hands, the objects on the floor, a room that wasn’t his. I got to work convincing myself the girlfriend was ugly, her hair that brassy orange-blond that hadn’t been dyed in a while. Or maybe it was supposed to look like that, bad: maybe it was cool and I didn’t understand it. Where was she when I was there? Where was she when I wasn’t? Had she been with him while I was getting drunk and going home with strangers because I wanted so badly to meet him in them? Would she be with him in the morning, while I was having an abortion? Would I ever tell him now? Maybe in writing, maybe like this.

I scoured the internet for pictures of her, each scrap of information delivering a fresh bright pain like what is left after being slapped. More, more. There was no limit to how much I could take. She went to fashion school. So she was an artist of sorts, I thought, the kind who can afford to play dress-up for a living. She could probably get a $700 abortion and pay her rent in Manhattan without issue, I thought, instead of writing a long apologetic text to her elderly landlord in Boston as I had. I bet she’d read A Dictionary of Color Combinations and knew the complexions and fabrics that composed the earth, she wore the right clothes and was invited to the right parties, she never got too drunk and lied to the people she loved, never asked her little brother for a ride when she took the wrong drugs in the wrong order and walked into the lake and couldn’t remember the way home. She was proof of something cheap and ugly and Midwestern in me. She did not practice softness and gentleness, it lived in her. She was a permanent object: she didn’t come and go, didn’t get bored and broke and impulsive. He could contain her and know her, and she was easy to love. I hated her immediately and completely: it was soulful, it was animal, it was exquisite and cruel. I put my hand on my belly. Inside me is all the power in the world, I thought, and tomorrow I will relinquish it.

(When I was a teenager, a man in a bar offered my school friend and me little yellow pills from a dime bag that he pulled from his pocket like a magic trick, all stupid and proud. He bought us tequila shots to wash them down. When we threw our heads back, I saw my friend toss her pill discreetly over her shoulder as she downed the shot. We bit into limes rubbed in salt, her with her wisdom and me with the pounding realization that I was not clever, I had swallowed the pill, I did not know anything about the world. She brought me back to her stepdad’s house, where I slept for 16 hours. It was the next evening when I got home, where my mother was too angry to look at me but too relieved to look away. I will not, she said, be made to sit around wondering if you are dead. You think you know everything, but you do not know even half of what could happen—)

Kate met me at the abortion clinic. It would be acceptable, I think, to write an earnest, tormented confession about abortion, or to remove the self completely and evangelize about choice. I got the distinct impression, ducking past the few protestors camped out in front of Planned Parenthood, that what they wanted was not for me to not have an abortion, but for me to take it as seriously as they did, to feel something humorless and sincere—remorse, ideally, but even the feminist’s equal and opposite sanctimony would do. But I did not care, not about them and not about this. That is what they hated, what they gathered to protest. Their creation story, the one that says the fetus is as complete and as alive and deserving of life as its host, is an invention of the last century. Before then, people who condemned abortion were concerned with female promiscuity, not an embryo’s right to life. I suspect that their intentions, while reworded, haven’t really changed. When I say that the pregnancy and its termination did not alter me in some dire, permanent way—that in fact it didn’t alter me at all—they do not believe me. On some level, no one believes me. On some level, I don’t believe myself. My sin against the protestors wasn’t having the abortion, but having it without being tortured by the choice. What about the hours of reckoning, contending with the guilt, weighing the karmic returns of letting this life grow or snuffing it out? I didn’t have them.

A ceiling tile over my head in the ultrasound room was painted to look like a blue sky stamped with fluffy cartoon clouds. It was a little condescending and a little sweet—like the nurse’s pink scrubs, or the counter-protestors outside the clinic who took great pride in shepherding me out of harm’s way. I lay on the exam table with my shirt pulled up. The nurse put cold Aquasonic gel on my stomach, her machine picking up the sound waves underneath. “Do you want me to tell you if there are multiple pregnancies?” Sure, I said. “You don’t have to know anything you don’t want to know,” she clarified. I knew that—this was Massachusetts, not my home state of Missouri, where what I was about to do had recently become a felony. But I am sick, sick and I want to know everything. More, please, more. “Do you want to know how far along you are?” Yes: six weeks. “Do you want to see?” Yes: she turned the screen to show me the sonogram. “Do you want me to print you a copy?” Yes, yes, I want everything, yes. I deserved a souvenir, something to show for my $700 problem and to show Kate in the waiting room. I was scared to be the keeper of this feeling, but curious too.

I remembered a scene from Joyce Carol Oates’s 2017 novel A Book of American Martyrs that went like this: an Evangelical preacher is on death row for the murder of an abortion-providing doctor. The killer’s wife, carrying her husband’s torch on the outside, leads a vigil for the unborn behind the local abortion clinic, pulling Ziploc bags of fetal remains out of a dumpster. The remains are “fleshy, meat-colored, damp with blood” like the graphic viscera of a schlocky slasher movie—some have heads, legs, mouths. They are half-baked, misshapen but visibly human; like entire pigs hanging in a butcher’s window, their resemblance to the living is on gruesome display. Of course, these are not real fetal remains, but props aimed to horrify and embolden the mourners—and, much like the giant humanoid fetuses on 1-800-LIFE billboards on the Missouri highways of my youth, they succeed in startling their audience.

I held the sonogram and examined the incoherent contours of light and dark. It was a little disappointing. I guess I had expected a picture of the world, where wool sprouted from the backs of lambs and at night the heat let up and the crickets sang for a mate; people slept together and died and wept and trembled like moons on water — any number of sentimental images strewn together, loosely conveying a life. But this was a picture of the folds and hollows of the body’s soft tissues, or the negative space where there are none. The living protest when we are killed—this did not even kick, or recoil as a flower might from the harsh sun. Hello speck, I said to it. It said nothing. Nothing had ever happened to it. Nothing, I guess, aside from being not wanted, up close and at a distance, by someone with an object permanence problem.

It had never run to catch a train, or felt eternity compressed into a moment when the whole world is a train and the train gets away. It was better than relief, to feel nothing for something. I too could be disaffected, I too could be cool. I could be as men had been to me, greedy, violent, groping for meaning at the bar. They were just sweet boys, their sorrows showing off for me in the dark.

Some notes-

The events mentioned in Odessa, TX are those of the true story of a teenage girl named Betty Williams. You can read original coverage of her case in The Odessa American, March 23, 1961.

Sanzo Wada (1883-1967) was a painter and costume designer whose work in color research lay the foundation for much of modern fashion and design. An interactive gallery of A Dictionary of Color Combinations is available online.

Names were changed (minus Kate’s).

Thank you, Kate.

I thought this was going to be an essay on object permanence—I spent the last several months immersed in the writings of Melanie Klein and object relations theory…and it is. In an interesting way.